Balanced dietary multi-supplements and pregnancy

Dietary supplements, before and during pregnancy but also during breastfeeding, help fetal growth and development, the better outcome of the pregnancy, optimization of the woman’s health and wellbeing, the prevention of post-partum depression and the improvement of the quality of the breast milk.

The intake of larger quantities of food in order to cover the needs in calories, as well as the increased absorption and the more effective utilization of the nutritives taking place during pregnancy, are usually adequate for covering the needs regarding most nutritives. However, vitamin and mineral supplements are indicated for a number of nutritives which, if they are to be taken in a specific quantity, cannot be associated with dietary overconsumption, as long as pregnant women take care when selecting a supplement, in order to avoid exceeding the maximum tolerance limits for a specific vitamin or a specific mineral.

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) per day for folic acid during pregnancy is 600μg. In order to avoid neural tube defects, women in reproductive age and pregnant women must, besides consuming folic acid through a diet with a variety of foods, consume daily 400μg of synthetic folic acid from enriched foods (cereals and other grains), supplements or both. In order to ensure suitable vitamin levels in blood for the time of the neural tube completion, supplement intake must start at least one month before conception. Research shows that abnormal folic acid metabolism may also play a role in Down’s syndrome and in other genetic abnormalities.

Pregnant women must be encouraged to consume foods rich in iron, such as lean red meat, poultry, fish, dried fruit and iron-enriched cereals. Wherever this is not possible, the USA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that all pregnant women take, already after their first visit to the gynecologist, a small dose of iron supplement daily (30mg daily). Although there are no definite data regarding the benefits of universal supplement consumption, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention support this position, because many women find it difficult to maintain adequate iron reserves during pregnancy. Moreover, the lack of iron during pregnancy can have negative consequences, while taking an iron supplement during pregnancy is not associated with significant risks for health. Balanced multi-supplements improve iron levels in the mother both during pregnancy and in the post-partum period, a fact that may prove particularly important when the period between two pregnancies is short. Iron may affect the absorption of other minerals. Consequently, it is recommended that women taking supplements with more than 30mg of iron daily, also take 15mg of zinc and 2mg of copper supplements. Taking zinc is necessary for the normal development of the fetus. Zinc is a component of hundreds of other enzymes and other proteins, hormones and neuropeptides. It also facilitates gene transcription and contributes in cell division, development, differentiation and in embryogenesis. It is directly linked with carbohydrate, protein and lipid metabolism enzymes. It is worth noting that it is a necessary component for the development of the central nervous system. The nutritional condition of the pregnant woman in zinc in the middle of the pregnancy seems to be particularly important for the correct development of the central nervous system (CNS) of the fetus and its subsequent mental condition as an infant.

During pregnancy, the additional needs in zinc are of 100 mg approximately. This is 5-7% of the total zinc in the body of a non-pregnant woman. The additional zinc is deposited in the fetus (57%) and in the womb (24%). The additional zinc needs during pregnancy can be covered through increase of the dietary intake and adjustments in its homeostasis. Most research has shown that there is no significant increase of dietary intake of zinc in pregnancy, with the result that homeostatic adjustments in the use of zinc constitute the main mechanism for covering the additional requirements in pregnancy. More specifically, zinc absorption increases by an average of 30% or 1 mg/ day, particularly in the second half of the pregnancy. From the 1 mg, 0,7 mg are transferred to the fetus, while the remaining 0,3 mg are removed with urine. Because of the increase of the renal glomerular filtration, higher excretion of zinc is observed during pregnancy. There is also no zinc release from the tissue of the pregnant woman, in order to help cover additional needs for it during pregnancy. Moreover, the mean serum zinc concentration decreases as the pregnancy advances and this may be due to hormonal changes or normal adjustments of the pregnancy or a combination of these factors. Pregnant women present an increased risk of zinc deficiency because of the increased normal needs during pregnancy. Serious zinc deficiency in the pregnant woman is associated with miscarriages, congenital deformities (e.g. anencephaly), pregnancy hypertension and pre-eclampsia, while milder forms of zinc deficiency are associated with low body weight at birth, intrauterine growth retardation, placental abruption, premature rupture of membranes, premature birth or prolonged pregnancy which may end up in a cesarean section, perinatal asphyxia etc. Zinc is a necessary co-factor for the transfer of immunoglobulins from the pregnant woman to the fetus through the placenta. Moreover, inadequate dietary condition of the pregnant woman in zinc may adversely affect vitamin A levels of the newborn, a key vitamin for its survival. Other negative effects of inadequate dietary condition of the pregnant woman in zinc are the child’s reduced memory, attention, cognitive and learning capacity.

The additional zinc administration for the improvement of the pregnancy outcome has shown contradictory results in the studies carried out. There are noteworthy studies showing that taking zinc may lead to increased birth weight, larger head circumference and faster physical growth of the newborn only when the pregnant woman had an inadequate dietary condition in zinc and body mass index <26 kg/m2 during conception. Consequently, the complementary administration of zinc has no protective action regarding low birth weight in overweight and obese women, but only in pregnant women with normal weight. The zinc supplement dosage used in the above-mentioned studies was 25 mg/day, which does not mean that it is the lowest effective dosage.

Zinc intake during pregnancy is recommended to be 15 mg/day, while its maximum intake limit is set at 35 mg/day. Although most studies maintain that its usual intake is lower than the recommended one (11 mg), there is no recommendation for supplementary administration. This happens because there is no evidence that its usual intake is so low as to limit the production of necessary substances for the health of the pregnant woman, the fetus and the baby. Rich zinc sources are products of animal origin, like veal, eggs, seafood. Other good sources are pulses, dried fruit and wholegrain cereals. Fruit and vegetables are poor zinc sources. Zinc in vegetable products is less bioavailable because of the presence of phytic acids and fibers.

Factors that may cause secondary zinc deficiency in pregnancy are those that inhibit its absorption (e.g. phytic acids, calcium), supplementary administration of elemental iron of over 60 mg/day and the factors that prevent its transfer to the placenta like smoking and alcohol. All these conditions reduce the concentration of zinc in serum and reduce its available quantity to the fetus. Pregnant women with the above-mentioned characteristics may take daily zinc supplements of 25 mg, in order to avoid deficiency complications. It is also recommended for pregnant women taking iron supplement of over 30 mg/daily to also take a zinc supplement of 15 mg/day, because of the inhibitory effect of iron in zinc absorption. Because the supplementary administration of zinc has adverse effects in copper metabolism, the administration of copper supplement of 2mg must accompany the zinc supplement.

Normal calcium requirements increase by 200-300 mg/daily during pregnancy. This increase may theoretically be satisfied by increasing dietary intake and intestinal calcium absorption, reduction of calcium excretion in urine and calcium mobilization from the bone mass of the pregnant woman. In reality however, during pregnancy the absorption of calcium increases significantly (2-3 times) through the gastrointestinal system, while calcium excretion through the kidneys is also greater, because of increased renal glomerular filtration. These increases occur at the beginning and in the middle of the pregnancy, anticipating the increased requirements of the fetus for the development of its skeleton observed in the third trimester. Additionally, the absorption and the formation of the pregnant woman’s bones increase as the pregnancy advances, while the concentration of osteocalcin in plasma decreases (bone formation marker) because of its intake through the placenta. An increase by 50-200% is also observed in bone turnover during pregnancy. Calcium concentration in serum decreases in this period because of the increased intravascular fluid volume and the subsequent dilution. The changes in calcium metabolism and bones during pregnancy are accompanied by increases in calcitriol (active vitamin D) and small changes of calcitonin and parathyroid hormone.

Calcium is necessary in pregnancy for the composition of the bones of the fetus, with 25-30 grams in total approximately to be taken by the fetus, mainly during the third pregnancy trimester. Consequently, the biggest part of the fetal skeletal growth takes place from mid-pregnancy and later, mainly in the third trimester. It is possible that the osteosynthetic activity of the pregnant woman during pregnancy depends on a variety of factors, like age and the number of previous births, her nutritional condition and her endocrine profile before pregnancy etc.

In the past, the recommendations to pregnant women were to increase significantly dietary intake of calcium in order to cover both the needs of the fetus and the needs of maintaining their bone mass. Contemporary research shows that two normal adjustments during pregnancy, the significant increase of calcium absorption and excretion, bring about a positive calcium balance in the pregnant woman, with the result that she does not have to take daily larger calcium doses in comparison with the period before pregnancy.

The recommended intake for a pregnant woman of over 19 years is 1000 mg/day. Pregnant adolescents have higher calcium needs because they must support their own bone growth. Therefore, recent recommendations for calcium intake by pregnant adolescent are for 1300 mg/day. Also, as critical changes in the pregnant woman’s physiology happen independently of the current calcium intake in pregnancy, it is important to stress the recommended intake of dietary calcium by the pregnant woman before pregnancy. However, some research studies in the USA have shown that pregnant women take a smaller dose of dietary calcium in comparison with the recommendations for pregnancy.

The administration of calcium supplements during pregnancy is safe up to 2500 mg/day (maximum). Pregnant women older than 35 years, pregnant women with a pre-eclampsia history, pregnant women with diabetes, renal insufficiency and chronic hypertension, pregnant multiparas and pregnant women from low socioeconomic classes have increased probabilities for pre-eclampsia during pregnancy. The exact factors included in pre-eclampsia pathology are not clear, but it is considered possible that changes occur in calcium metabolism. Possible metabolic disturbances in calcium metabolism include reduction of the concentration of serum active vitamin D, reduction of serum calcium ions concentration and reduction of calcium excretion. Calcium is the micronutrient which has been studied most in relation with the occurrence of pre-eclampsia and pregnancy hypertension. Epidemiological studies show that there is a correlation between reduced calcium intake and pre-eclampsia. These observations have led to the assumption that the frequency of pre-eclampsia can be limited to pregnant populations with reduced calcium intake after supplemental administration of calcium preparations. 13 randomized controlled clinical intervention studies showed an average reduction by 32% of the frequency of pre-eclampsia occurrences after supplementary average administration of 2 g/day of calcium. This effect was more pronounced in pregnant women’s groups with low calcium intake. However, in most of these studies the pregnant women’s sample was small, with the result of increased error probability. The largest study to date, in which 4589 pregnant Americans participated, showed no positive effect from the supplementary calcium administration (2000mg/day) in blood pressure. However, in this study the pregnant women’s sample was characterized by adequate calcium intake. In conclusion, the studies up to date produce contradictory outcomes regarding the effect of calcium supplements in the prevention or treatment of pre-eclampsia or pregnancy hypertension. It appears that the daily intake of calcium supplements benefits pregnant women with low dietary calcium intake or characterized by high risk of presenting pregnancy hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Low calcium intake is usually due to inadequate consumption of dairy products or foods enriched in calcium. Further studies are required in order to determine the ideal calcium supplement dosage which will contribute in the prevention of the above-mentioned pathological conditions.

It seems that calcium intake has a significant effect on the newborn’s weight. More specifically, the larger the calcium intake, the more the pregnancy term is prolonged, the fetal development is supported and therefore underweight newborns are avoided. Also, children whose mothers had low calcium intake in pregnancy and took calcium supplements during the pregnancy, had lower arterial pressure at the age of 7 years, in comparison to children whose mothers had reduced calcium intake during pregnancy and took no supplement. Of course, it should be pointed out that the above-mentioned correlation is mainly true for overweight children aged 7. Consequently, reduced calcium intake during pregnancy may lead to hypertension in childhood, which can only be prevented if the pregnant woman takes a calcium supplement during pregnancy. additionally, the dairy group is negatively associated with the occurrence of miscarriages. In other words, the lower the dairy product consumption (consequently calcium consumption) in pregnancy, the higher the risk for miscarriage in pregnancy. Other studies say that the intake of dietary calcium by the pregnant woman is important for the bone mineral content of the fetus, even in societies of abundance, where food is rich. The best way to ensure smooth bone mineral content of the fetus is through the intake of dietary calcium by the pregnant woman, as dietary sources rich in calcium are also rich in other nutrients necessary for the health of the bones of the fetus. Also, supplementary calcium administration to pregnant women with adequate dietary calcium intake, does not seem to increase the concentration of fetal bones in metals.

No change was observed in the levels of mineral phosphates in the bones and in the serum during pregnancy. Consequently, supplementary intake of phosphorus during pregnancy is not recommended. The recommended intake is 700 mg/day in pregnant women aged 19-50 years and 1250 mg/day in pregnant adolescents. Its maximum intake in pregnancy had been set at 3500 mg/day. Most foods contain phosphorus; therefore, its insufficiency is rare during pregnancy. No study until today has examined the effect of dietary phosphorus in saving metal elements in pregnancy or in the outcome of both the health of the pregnant woman and the baby.

Magnesium is stored in bones at its highest proportion. The amounts of magnesium which are biochemically active are concentrated in neural and muscular cells. Magnesium concentration in serum during pregnancy remains stable until the final stage of the pregnancy, when it starts constantly diminishing. Studies have shown that insufficient magnesium intake is a frequent occurrence during pregnancy and has been correlated with delayed intrauterine development, premature birth, low birth weight, pre-eclampsia and neuro-muscular dysfunctions. Studies in developed countries have shown that supplemental administration of magnesium improves various perinatal parameters, like low birth weight, pre-eclampsia and delayed intrauterine development. However, there has not been unanimity until today regarding the role of supplemental administration of magnesium in the prevention or occurrence of birth complications. The recommended daily intake of magnesium in pregnancy is 400 mg for ages below 18 years, 350 mg for ages of 19-30 years and 360 mg for ages of 31-50 years. We observe that the needs do not increase significantly in relation to the pre-pregnancy period and this small increase can easily be covered through dietary choices which emphasize green leafy vegetables, wholegrain cereals, pulses and dried fruit. The maximum intake limit in pregnancy has been set at 350 mg/day. There are also large epidemiological studies which suggest that increased vegetable intake during pregnancy is related to low miscarriage risk. Obviously, magnesium – a key ingredient in vegetables – contributes in this correlation.

Sodium metabolism changes during pregnancy. Blood volume increase, amniotic fluid volume increase and increased sodium needs of the growing fetus during pregnancy demand increased sodium retention. The total natrium in the body is calculated to increase by 900-950 meq (25 gr. of sodium, 60 gr. ΝαCl) during pregnancy by an average increase of 4 meq/day. The concentration of serum sodium in pregnancy remains almost stable. The increased renal glomerular filtration, progesterone and the natriuretic factor cause increase in the excretion of sodium by the kidneys. In contrast, aldosterone, estrogens and the renin-angiotensin system decrease renal sodium excretion. Studies have shown that in pregnancy the preference for salt and salty foods increases. In this, pregnancy hormones like progesterone and estradiol play a part, showing that changes in the preference for salt in pregnancy have an endocrine basis.

Increased fluid retention observed during pregnancy reduces the needs of the body for sodium in a way. The real needs for sodium are very small (200-400 mg/day) for pregnancy, in comparison to the usual daily intake which is 2300-6900 mg/day. For pregnancy only 70 mg/day are added to the basic needs (the total needs of 20000mg divided by the total of 300 days). Studies in laboratory animals have shown that reabsorption mechanisms in the kidney underperform when dietary sodium is reduced significantly. Hypertension conditions owed to pregnancy must not be treated by extremely reduced sodium intake, because limiting sodium not only does not prevent these occurrences, but on the contrary, it causes complications. Moreover, it must be taken into account that pregnant women do not “tolerate” and do not conform easily with very low-sodium diets. Any diet that is adequate in energy can fully cover sodium needs. It is therefore not necessary to recommend unlimited salt intake during pregnancy. The recommendation of unlimited intake presents risks for 15-20% of women who are susceptible to idiopathic hypertension. The final advice is to individualize recommendations in every case.

There is scientific evidence in international literature linking magnesium with the avoidance of cramps in the lower extremities, the successful control of arterial pressure, the prevention of premature uterine contractions, which may lead to premature birth and the successful control of sugar levels in blood. One of the more “feared” pregnancy pathologies is pre-eclampsia. This pathology is characterized by the appearance of hypertension, edemas, which are not limited in the lower extremities, but are all over the body and the face and the appearance of protein in urine. In extreme cases the mother presents neurological disorders characterized by seizures, eyesight disruptions and intense headache. In some cases, disorders in clotting and in liver function also appear. The occurrence of pre-eclampsia may put even the woman’s life at risk. The first measure for arresting the development of this pathology, if symptoms are considered intense, is to bring about a birth or a cesarean section. Still, this measure is often not sufficient and for this reason magnesium sulphate is administered intravenously in combination with other medicines. According to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), in the USA, magnesium needs increase during pregnancy. Specifically, a woman aged between 19 and 30 years needs daily 310mg magnesium, while during pregnancy she needs daily 350mg, the corresponding quantities for a woman aged 31 to 50 years are 320mg and 360mg.

The consumption of a multivitamin and mineral supplement is recommended during pregnancy in many occasions. Pregnant women who smoke or abuse alcohol or drugs must take a multivitamin supplement. Supplements are also recommended for women with iron-deficiency anemia or low-quality diets, as well as those who consume very little or no animal products (like vegetarians). In the latter case, it is of particular importance to take a vitamin B12 supplement, mainly because taking a folic acid supplement may mask the symptoms of lack of vitamin B12. Finally, women carrying two or more embryos must also take a multivitamin and mineral supplement.

Selenium is a component of many important antioxidant enzymes; therefore, its most important function is to protect the body from oxidative damages. It is also necessary for the use of iodine in the production of thyroid hormones for the function of the immune system and the reproductive system. Manganese is necessary for bone formation and energy metabolism. It is also a component of an antioxidant enzyme which prevents cell damage from free radicals.

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is the main form of vitamin D in the body. It is the form which is produced in skin and can be found in some foods and dietary supplements. Although there are other forms of vitamin D, like vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol), studies have shown that our body metabolizes vitamin D3 more effectively than vitamin D2. Taking into account the multiple undesirable effects of vitamin D deficiency in various health aspects, the administration of a vitamin D supplement is of utmost importance. Meta-analyses of studies show that supplementing vitamin D during pregnancy is safe and improves the condition of vitamin D and calcium, thus protecting health. There are no specific instructions regarding supplementing vitamin D for women or men with endocrine disorders and infertility. Current instructions recommend taking vitamin D 400 to 800 IU daily, while even 1000IU daily may be needed if there are low levels.

- British Nutrition Foundation, Nutrition for pregnancy. 2019

https://www.nutrition.org.uk/healthyliving/nutritionforpregnancy.html

- Department of Health, UK Chief Medical Officers' low risk drinking guidelines. 2016

- National Health Service, Start 4 life, 2019, https://www.nhs.uk/start4life/pregnancy/

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Healthy eating and vitamin supplements in pregnancy. 2014

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, Advice on fish consumption: benefits & risks. 2004

- The British Dietetic Association, Food fact sheet: pregnancy. 2016,

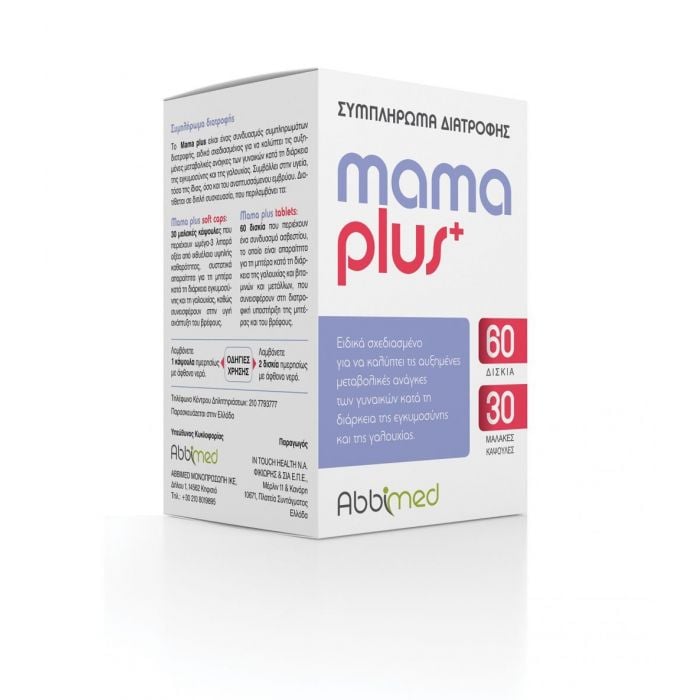

| Brand | Abbimed |

|---|---|

| Availability | 1-3 business days |

| Flammable | Νο |

| Vegan | No |

| Off from Original Retail Price | 21 |

| Lowest 30-day Price | 35.87 |

| Audience | Women |

| Content | 60tabs - 30 Caps |

| Ages | All |

| Skin Types | All |

The information below is required for social login

Sign In

Create New Account